System.out.println("End of Maven init: " + System.currentTimeMillis());May 21, 2023

mvnd - the Maven Daemon

Maven is a build tool for Java and other languages targeting Java Virtual Machine (JVM). The declarative approach to defining builds belongs to its main strengths. Even basic knowledge of Maven principles allows understanding basically any third party project. It is well established, rather stable and has a rich ecosystem of plugins. It is also very important for defining the de facto standard for publishing and consuming libraries. Maven Central and its artifact metadata formats are used and respected throughout the JVM world.

Maven has some well known downsides though:

-

pom.xmlfiles are often criticized as being too verbose. -

Maven performance is not on par with Gradle, especially in incremental and iterative scenarios.

-

Maven parallel builds are hard to use, because the console output is a mishmash of randomly mixed lines from different module builds.

Let’s have a look how Maven Daemon addresses the latter two points.

JVM performance basics

Most of us, Java developers, know that Java is fast, but it needs some warm up time to unveil its full potential. On one hand, this is caused by the fact that booting a JVM application costs some time and on the other hand by the way how Just in Time (JIT) compilation works in JVM.

Maven boot costs

Let’s have a look at the boot costs first.

For Maven, they can be quantified through a simple experiment.

In Maven source code, we find the location where Maven starts its own build duration measurement.

That’s the baseline for the famous BUILD SUCCESS/Total time: message at the end of every Maven build.

We can say that this is the point where Maven starts doing something useful.

Everything that happens before can be considered a boot up cost.

So we place the following statement around there

and invoke something as simple as mvn clean prepending it with a shell time output in milliseconds, like this:

$ echo $(($(date +%s%N)/1000000)) && mvn cleanIt outputs two numbers.

On my Lenovo P1 Gen 3 laptop those were 1634117024986 and 1634117025765 respectively.

Subtracting them gave the result of 779 milliseconds.

That’s the time needed to boot the JVM and load all classes necessary for Maven to start doing something useful.

Three quarters of a second.

That’s quite a lot, isn’t it?

Just in Time (JIT) compilation costs

Java source files are compiled by javac to bytecode at build time.

However that’s not the kind of code runnable on any physical processor.

The bytecode is yet to be translated to instructions comprehensible to some given processor.

This initially happens "on the fly", as the JVM is executing the methods of the application.

Every method is first executed in this basic interpreter mode.

Only if some method is executed often enough (becomes warm), the JVM decides to compile it using the quick compiler.

Once the given method gets hot, i.e. it is executed very often, the JVM compiles it using the optimizing compiler.

Apparently, the JIT compilation requires some computing resources itself.

Hence to make the application faster, it slows it down first by spending CPU time on the compilation and optimizations.

What is the impact of this on Java build tools?

It is quite substantial, because builds are rather short living processes. The boot costs of 0.78 seconds may well translate to a substantial portion of the overall build duration.

As for the effect of JIT compilation, the code of a short living build is either running in the slow interpreter mode or if JIT compilation kicks in at all, its overhead can hardly pay back before the process exits.

Having a background process (daemon) that survives the individual builds is a very straightforward solution to both of these problems. This background process then hosts the actual build and the command line utility is just a thin client for it.

While Gradle has it since long, it is rather new in Maven.

Let’s try it out.

Installation

Maven Daemon needs to be installed separately from Maven. The installations of Maven Daemon and Maven do not interact in any way. You can have both or just one of them on your machine.

Maven Daemon can be installed in several ways. Using some of the following package managers is perhaps easier than downloading a ZIP file from https://downloads.apache.org/maven/mvnd:

Parts of Maven Daemon

As sketched above, you need two things to leverage the concept of daemon: the command line client and the background process.

mvnd - the client

In case of Maven, the client is a brand new program called mvnd (or mvnd.exe on Windows) that has little in common

with the traditional mvn script.

Although it is written in Java, it is compiled to native executable using GraalVM.

To be precise, this is the case only for platforms supported by GraalVM.

There is a shell script (mvnd.sh) wrapping mvnd-client.jar for the platforms unsupported by GraalVM.

Why did we bother to port the client to GraalVM? Except that it was fun, it has also brought some performance benefits. GraalVM native executables are known for extremely fast boot up times and low memory footprint. That’s exactly what we needed. Besides, by having a single client executable, we eliminated another slowing down process in the execution chain: the shell script.

So we have the mvnd command line client that starts quickly.

What does it actually do?

First, it looks whether some Daemon process is running and whether it is free for accepting build requests.

It does so by reading the Daemon registry stored in ~/.m2/mvnd/registry/<version>/registry.bin.

If there is no free Daemon, a new one is launched by the client.

Then the client connects to the Daemon through a network socket

and passes the command line parameters along with the environment of the current shell to the Daemon.

The Daemon accepts the request and starts executing it. As the build proceeds, it sends notifications about the progress back to the client. The client visualizes the state of the build in its text-based user interface.

Daemon

The Daemon process is a traditional JVM.

It embeds a specific Maven version.

The Maven version cannot be changed in any other way than by switching to another mvnd version.

The Daemon reads pom.xml files, loads plugins, downloads dependencies and all the other things that Maven usually does.

The main difference against stock Maven is that the Daemon does not exit upon build termination.

It stays alive listening on the network socket and waiting for new requests from clients.

Another difference against standard Maven is that Maven Daemon keeps a cache of classloaders holding references to Maven plugin classes. Hence if you keep building the same project with the same plugins during the day, chances are high that you’ll eventually run the optimized code produced by the second level JIT compiler.

Of course, the Daemon terminates at some point. The exact point in time depends on whether the given Daemon is the only one running. In such a case, it exist after 3 hours of being idle. This value is configurable - see the Configuration section below.

If there are other Daemons running that were idle for longer time than the current Daemon, then the current Daemon exists much faster - the default is 10 seconds and it is also configurable.

The state of the running Daemons can be inspected using mvnd --status command.

Here is an example output:

$ mvnd --status

ID PID Address Status RSS Last activity Java home

5a12 3434 inet:/127.0.0.1:46675 Idle 721m 2023-05-21T20:12:16.905 ~/java/17.0.5-tem

56fd 3181 inet:/127.0.0.1:34947 Busy 7g 2023-05-21T20:11:57.953 ~/java/17.0.5-temNote that the RSS column shows the amount of memory occupied by the given Daemon process.

All running Daemons can be stopped by invoking

$ mvnd --stopParallel by default

Unlike standard Maven, mvnd builds multimodule projects in parallel.

The default number of build threads is given by the expression Runtime.getRuntime().availableProcessors() - 1.

Another condition is that the dependency relationships between the modules in the current source tree must actually allow a parallel build.

For example, if there are three modules A, B and C to be built

and the dependencies look like the following

A

/ \

B C (Lower depends on upper)then the module A is built first.

After that, the modules B and C can be built in parallel.

This kind of parallel execution brings substantial speedups in "wide" module graphs where there are many siblings having a few common dependencies.

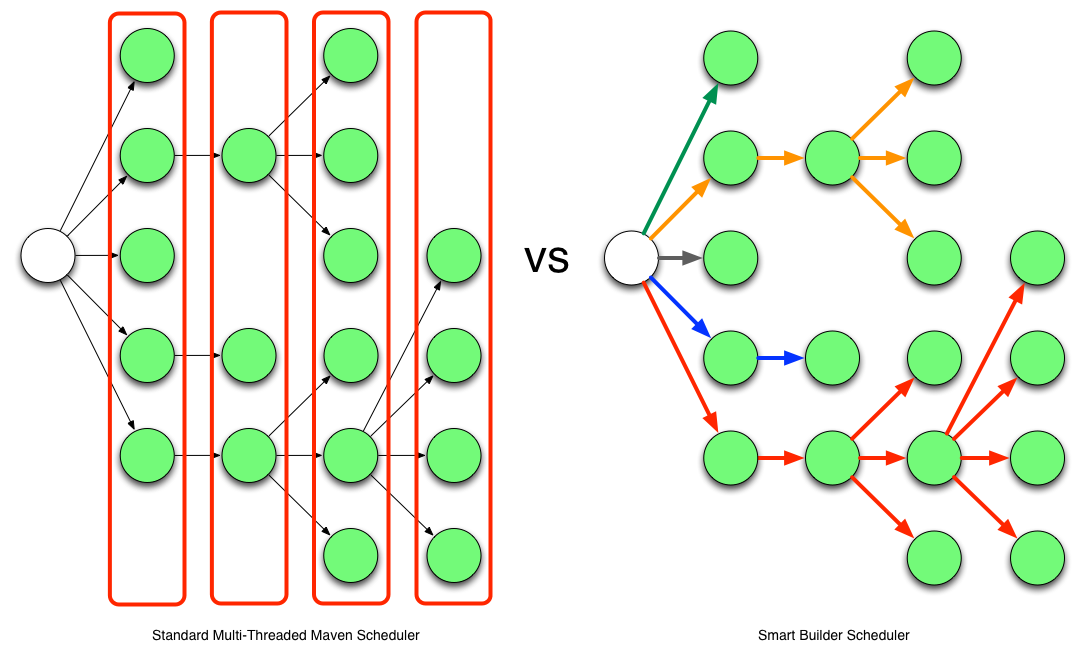

Smart builder

Maven has pluggable builders since version 3.2.1. Those are strategies for scheduling and building modules. Standard Maven offers two implementations:

-

singlethreaded(default) -

multithreaded- used with-T/--threadscommand line option

Maven Daemon uses a third builder called Takari Smart builder.

Its authors characterize it as follows:

The primary difference between the standard multi-threaded scheduler in Maven and the Smart builder is illustrated below.

Figure 1. Multi-threaded builder vs. Smart builder

Figure 1. Multi-threaded builder vs. Smart builderThe standard multi-threaded scheduler is using a rather naive and simple approach of using dependency-depth information in the project. It builds everything at a given dependency-depth before continuing to the next level.

The Takari Smart Builder is using a more advanced approach of dependency-path information. Projects are aggressively built along a dependency-path in topological order as upstream dependencies have been satisfied.

Benchmarks

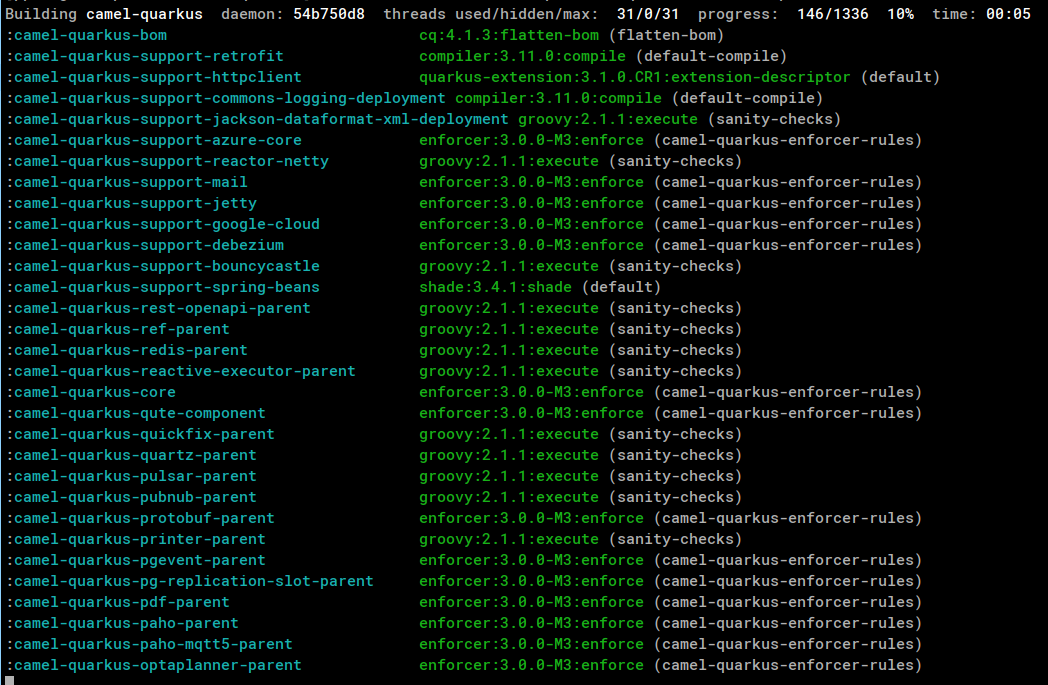

Camel Quarkus is a project where mvnd speed gains are visible especially well:

it has 1336 Maven modules and its module graph is rather flat and wide.

The test machine’s CPU was AMD Ryzen 9 5950X with 16 cores and 32 virtual threads.

Here are the build durations:

| Run no. | Command | Duration min:sec | Speedup |

|---|---|---|---|

mvn clean install -Dquickly¹ |

2:42 |

(baseline) |

|

1 |

mvnd clean install -Dquickly |

0:56 |

2.9x |

2 |

mvnd clean install -Dquickly |

0:48 |

3.4x |

3 |

mvnd clean install -Dquickly |

0:46 |

3.5x |

¹) -Dquickly disables plugins non-essential for a build that previously passed all checks on the CI,

such as tests, source formatting, enforcer, etc.

You may want to check this video

or slides

for more details about what -Dquickly does exactly.

The effect of the parallel build can be seen very well when comparing the baseline mvn run

with the first (on a cold JVM) mvnd run.

The mvnd build is 2.9 times faster thanks to the parallel build execution.

The effects of not restarting the warmed-up JVM can be observed when comparing the subsequent runs of mvnd:

the second mvnd run is 8 seconds faster than the first one and the third is even 2 more seconds faster.

This gradual acceleration is caused by the fact that with every iteration, less time is spent by JIT compilation

and the already JIT-compiled code runs faster.

Single module builds

We have demonstrated the mvnd speed gains for large multimodule builds.

But some folks do not build large multimodule projects at all.

There are also small and single module projects.

Or one can build a single module within a hierarchy.

Would there be any speed benefits there?

Let’s have a look at an example. Gizmo is a single module project having 50 main Java classes and 40 test classes.

| Run no. | Command | Duration sec | Speedup |

|---|---|---|---|

mvn clean install -DskipTests |

2.86 |

(baseline) |

|

1 |

mvnd clean install -DskipTests |

3.24 |

0.88x |

2 |

mvnd clean install -DskipTests |

0.61 |

4.66x |

3 |

mvnd clean install -DskipTests |

0.52 |

5.53x |

There is no gain from parallel execution here because we build just a single module. All we can see are the gains from reusing the warmed-up Daemon JVM.

We see that the first mvnd run is slower than the mvn baseline.

This can be explained through the overhead caused by starting the Daemon and connecting to it through a network socket.

But already the second mvnd build is 4.66 faster than the mvn baseline.

0.61 seconds vs. 2.86 seconds is a difference clearly perceivable by a human.

The third one is even faster.

0.52 seconds is pretty snappy for this kind of build.

Configuration

The behavior of Maven Daemon can be customized in many ways. The options can be passed either via command line or can be stored permanently in one of the following locations (in descending order of precedence):

-

${maven.multiModuleProjectDirectory}/.mvn/mvnd.properties -

${user.home}/.m2/mvnd.properties -

${mvnd.home}/conf/mvnd.properties

All configuration options and command line parameters can be listed via

$ mvnd --helpIt makes little sense to list them all here. Let us pick a few interesting ones.

All stock Maven options, such as -am/--also-make, -B/--batch-mode, -D/--define, -P,--activate-profiles, -v/-version, etc.

are supported also by mvnd.

--completion bash - the completion for Bash shell. You may want to add source <(mvnd --completion bash) to your ~/.bashrc or ~/.bash_profile.

-Dmvnd.serial/-1/--serial - use one thread, no log buffering and the default project builder to behave like a standard Maven.

Default: false

Discriminating start parameters

When describing the way how client looks for an idle Daemon, we omitted an important detail: the discriminating start parameters. Those define the essential characteristics of the Daemon, such as the Java installation path, maximum heap size, etc. which make it exclusive for some given build tasks.

For example, if I set JAVA_HOME to my Java 11 installation directory for the current shell,

I do not want mvnd to pick a Daemon running on any other Java,

even if such Daemon is idle.

I rather want mvnd to always pick a Daemon running on this exact Java even for the price of starting a new Daemon.

Here are some discriminating start parameters along with a short description what they do:

-Djava.home=<path> - Java home for starting the daemon.

Env. variable: JAVA_HOME

-Dmvnd.idleTimeout=<duration> - a time period after which an unused Daemon will terminate by itself.

Default: 3 hours

-Dmvnd.duplicateDaemonGracePeriod=<duration> - period after which idle duplicate Daemons will be shut down.

Duplicate Daemons are daemons with the same set of discriminating start parameters.

Default: 10 seconds

-Dmvnd.maxHeapSize=<memory_size> - the -Xmx value to pass to the Daemon. This option takes precedence over options specified in -Dmvnd.jvmArgs.

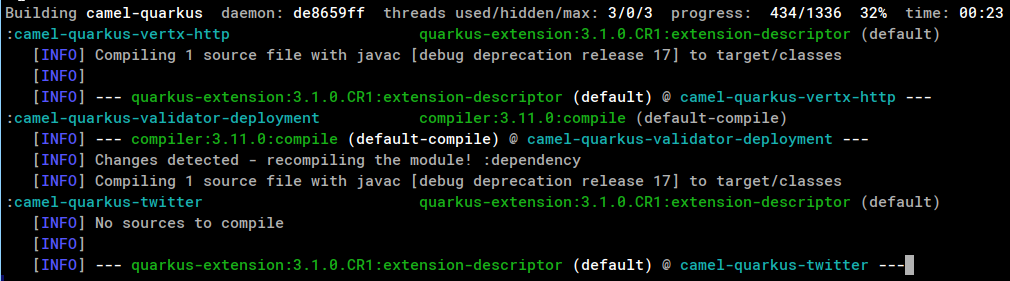

UI shortcuts

The text based user interface (UI) of mvnd supports a few shortcuts.

+ reveals more rolling log lines for the individual builder threads

while - reduces the number of rolling lines.

A UI state with zero rolling lines (default) is shown on the image above.

Below, you can see a UI state with three rolling lines per builder thread:

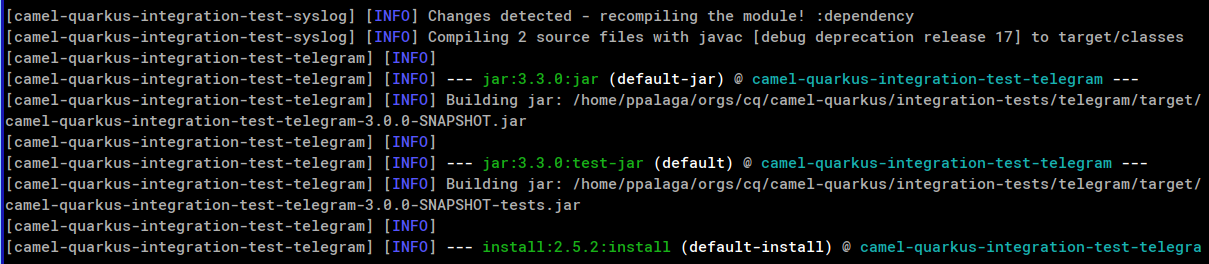

CTRL+B toggles between threaded (default, see above) and rolling views.

The rolling view can be seen below:

Note that every line is prefixed with the name of the module from which it originates.

Common issues

When you start using mvnd in a project that was never built in parallel, you may hit some of these common issues.

Hidden dependencies

Let’s assume that the modules in your project depend on each other as shown in the graph below:

A

/ \

B C (Lower depends on upper)As long as you use the serial builder, the modules are always built in the same order

and each module is fully built before any subsequent module built is started.

Hence the order is always A, B, C.

It is very easy to start relying on this constant and strictly serial ordering.

For example the build of module C could be reading a file in B's target folder.

Or C's tests could dynamically read an artifact produced by B from the local Maven repository.

All these assumptions won’t hold anymore once you switch to a parallel builder.

B can be built in parallel with C.

As a consequence of that strange exceptions may occur.

The build of C may throw a FileNotFoundException if the desired file is not yet there in B’s `target directory.

Or you may see a ClassNotFoundException if the build of C opens an unfinished jar that is just being produced by B.

A simple and straightforward remedy would be to force serial build by using -1/--serial parameter.

Another option is to make the dependency explicit.

If you do not want to propagate the dependency to runtime, you can use the test scope

and exclude all transitives as follows:

<dependency> <!-- Add this in C -->

<groupid>org.my-group</groupid>

<artifactid>B</artifactid>

<version>${project.version}</version>

<type>pom</type>

<scope>test</scope>

<exclusions>

<exclusion>

<groupid>*</groupid>

<artifactid>*</artifactid>

</exclusion>

</exclusions>

</dependency>This won’t add any real dependency to C but it will guarantee that B is fully built before C.

Broken plugins

Plugins may do all kinds of bad things that need to be avoided in parallelized environments. Maintaining mutable global state (via static field or system property) is a typical example that will inevitably lead to issues once the shared resource is accessed concurrently.

In such situations, the -1/--serial command line parameter may help again.

Reporting the issue to the plugin maintainers might however bring better results in the long term.

Wrap up

We have introduced Maven Daemon - a relatively new implementation of an older idea known from other build tools. Its main purpose is speeding up the builds by keeping the builder JVM warm across multiple subsequent builds.

Links

-

Source code, documentation, issues: https://github.com/apache/maven-mvnd

-

Downloads: https://downloads.apache.org/maven/mvnd